A darknet trader is illegally selling the Medicare patient details of any Australian on request by “exploiting a vulnerability” in a government system, raising concerns that a health agency may be seriously compromised.

An investigation by Guardian Australia can reveal that a darknet vendor on a popular auction site for illegal products claims to have access to any Australian’s Medicare card details and can supply them on request.

The seller is using a Australian Department of Human Services logo to advertise their services, which they dub “the Medicare machine”.

Medicare card details are not publicly available. They are valuable to organised crime groups, because they allow them to produce fake physical Medicare cards with legitimate information that can then be used for identification fraud.

These identification cards have been used by drug syndicates to buy goods and lease or buy property or cars. The card details could also be used to defraud the government of Medicare rebates. In 2015 a police strike force targeted a group that was using Medicare card details to direct rebate payments into fraudulent bank accounts.

Organised crime groups regularly use darknet auction services, which are more difficult for law enforcement agencies to track because they are not indexed or searchable like other parts of the internet.

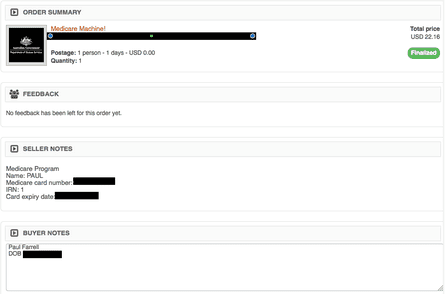

The darknet vendor has sold at least 75 Australians’ Medicare card details – describing them as “marks” – since October 2016. The listing page suggests they may have also been selling a large number before October 2016 but were forced to change their method for accessing the data.

The price for purchasing an Australian’s Medicare card details is 0.0089 bitcoin, which is equivalent to US$22.

Guardian Australia has verified that the seller is making legitimate Medicare details of Australians available by requesting the data of a Guardian staff member.

The darknet vendor says they are “exploiting a vulnerability which has a much more solid foundation which means not only will it be a lot faster and easier for myself, but it will be here to stay. I hope, lol.”

The listing continues: “Purchase this listing and leave the first and last name, and DOB of any Australian citizen, and you will receive their Medicare patient details in full.”

The vendor said they would soon create a “mass batch requesting of details”.

The seller is listed as a highly trusted vendor on the site and has received dozens of positive sale reviews.

“Man this guy is hooked up, from feetup he teed up, im impressed,” one buyer in December 2016 wrote.

“One of the best ozzy vendor,” another wrote in November 2016.

Guardian Australia has chosen not to identify the location of the listing or the specific auction site. It made the Department of Human Services, Department of Health, Australian federal police and information commissioner aware of the breach before publication.

The precise method the darknet seller is using to obtain the Medicare details remains unknown and may be difficult for government agencies to track.

The Department of Human Services is the primary agency that manages Medicare. However, the Department of Health would likely also have access to the Medicare card records of all Australians. It is also possible the information could have been obtained from another agency or organisation.

The reference to “exploiting a vulnerability” suggests that the Medicare records are being accessed in real time, which is likely to cause serious concerns within health government agencies about whether their systems are compromised.

The unlawful access of government information can constitute a computer crime offence under the commonwealth’s criminal code. The vendor’s use and disclosure of this information could also be an offence under the Privacy Act 1988 (commonwealth) or the Healthcare Identifiers Act 2010 (commonwealth).

A spokeswoman for the Department of Human Services said the agency was working with other government security agencies to investigate the sale of Medicare records.

“The department does not comment on cyber operations, however will confirm that investigations into activities on the dark web continually occur,” she said.

“The department takes the security of personal data extremely seriously. Thorough investigations are conducted whenever claims such as this are made.”

“The department takes every precaution to protect the sensitive information of Australians, and to safeguard the payments we make on behalf of the Australian government.”

A spokesman for the Australian federal police said the agency would not comment on whether it was investigating the matter.

The Office of the Australian Information Commissioner declined to comment.

The breach was uncovered shortly after the Australian government passed mandatory data breach notification laws for government agencies and private companies.

These laws make it compulsory for government agencies to notify the privacy commissioner of certain types of data breaches. The new laws have not yet come into force and will take effect in February 2018.

The Australian government has suffered a series of embarrassing data breaches in recent years.

In 2015 the personal details of world leaders at the last G20 summit were accidentally disclosed by the Australian immigration department, which did not consider it necessary to inform those world leaders of the privacy breach.

In February 2014 the agency also inadvertently disclosed the personal details of almost 10,000 people in detention – many of whom were asylum seekers – in a public file on its website.